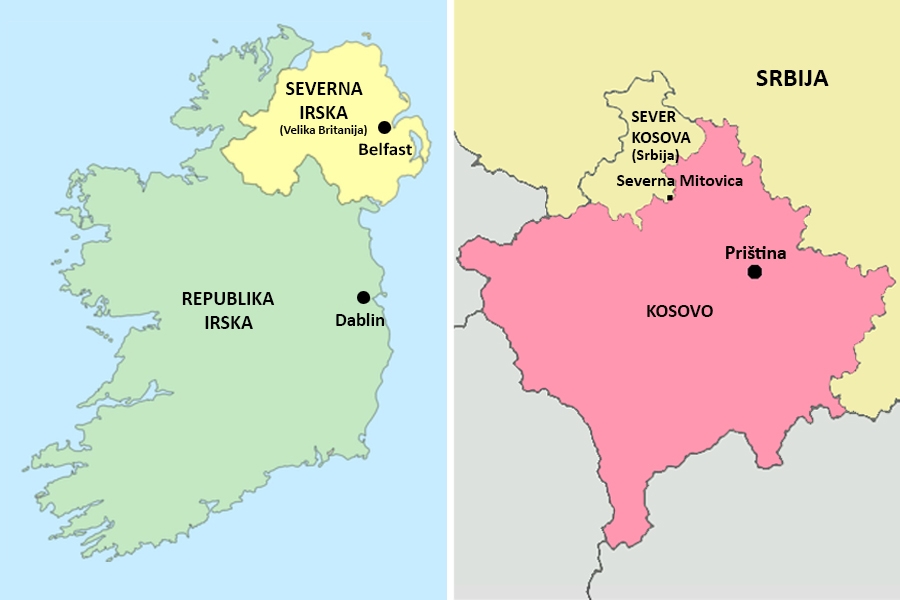

Does Northern Ireland offer a solution to the problem of northern Kosovo, as some diplomats have suggested? Perhaps – and not just because they are both ‘northern’ and disputed.

Does Northern Ireland offer a solution to the problem of northern Kosovo, as some diplomats have suggested? Perhaps – and not just because they are both ‘northern’ and disputed.

Ireland pressed for independence at the start of the twentieth century which, after a struggle, London eventually accepted. However, this was fiercely resisted by the predominantly Protestant population in the north (mainly descendants of emigrants from Scotland) who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom. London’s solution was to partition the island of Ireland, retaining the north and ceding the rest.

This worked for a while but did not resolve matters because the decision to partition Ireland was bitterly opposed by those Catholics who remained in the north, and whose numbers steadily grew relative to the Protestants.

Eventually, this opposition gave rise to a violent terrorist campaign, led by the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which aimed to pressurise London into surrendering Northern Ireland - and a counter-campaign by Protestant paramilitaries, backed by London, to crush the IRA.

‘The Troubles’, as this period was known, finally ended in 1997 when the various exhausted parties realised they could not achieve their various goals by means of violence. Instead, they agreed to a compromise package known as the Good Friday Agreement in which Northern Ireland remained formally a part of the UK but gained effective self-governance.

In addition – and this was the key innovation – the UK agreed to ‘share’ sovereignty over the province with the Republic of Ireland by giving the latter a voice in Northern Ireland’s internal affairs, dismantling all infrastructure on the border and encouraging extensive cross-border contacts.

As a consequence, Northern Ireland’s Catholic population – many of whom had dual citizenship - could effectively live as citizens of the Irish Republic while physically residing in the province, and its Protestant population could continue to live in a region which was formally a part of the UK.

Any latent contradictions were massaged by money, goodwill and recognition by almost everyone involved that there was no viable alternative to this compromise, at least for the time being.

So where does that leave Kosovo?

When diplomats talk of a ‘Northern Irish solution’ to the status of northern Kosovo, they no doubt have in mind some analogy to the Good Friday Agreement. Northern Kosovo remains a part of Kosovo while gaining formal autonomy, and sovereignty over the region is ‘shared’ between Belgrade and Prishtina. Meanwhile, Serbia formally recognises the entirely of Kosovo, both north and south.

So far, so good - except that there are three fundamental problems with this ‘solution’.

For one thing, the issue in Northern Ireland and northern Kosovo is not the same. In the former, two communities, roughly equal in size with no clear territorial division between them, cannot agree which state they want to be part of. The Good Friday Agreement solves that by offering a ‘third way’ compromise.

By contrast, in northern Kosovo, almost all the inhabitants belong to one group – the Serbs – who overwhelmingly want northern Kosovo (and the south) to be fully a part of Serbia. Since the problem is not the same, a solution based on the Good Friday Agreement is not the solution.

A second problem is that any solution in which northern Kosovo remains part of an independent state of Kosovo is unacceptable to Serbia which is not under any particular pressure to shift its position, except from a declining EU. This contrasts with the UK, which faced a 25-year campaign of terror.

The Serbian government has said that its condition for recognising Kosovo is that the north is fully incorporated into Serbia itself. And, as opinion polls make clear, even that is highly controversial. So, a solution which is essentially a minor modification of the Kosovo government’s position – that the north can (perhaps) become part of a Community of Serb Municipalities in return for Serbia’s recognition of the whole of Kosovo – is not politically sellable.

Third, and most importantly, a solution in which northern Kosovo remained a part of Kosovo would not actually be a Northern Irish solution at all. For the solution to be analogous, northern Kosovo would have to remain a part of Serbia, as Northern Ireland is a part of the UK, not of the breakaway state. But that is not the idea which diplomats are proposing – just the opposite, in fact.

In theory, northern Kosovo could become an autonomous region of Serbia, subject to some kind of ‘shared sovereignty’ between Belgrade and Prishtina. But since there are almost no Albanians living in the region, this would be a meaningless nonsense. On the face of it, the Good Friday Agreement has little to offer Kosovo.

Go back further in time, however, and the case of Northern Ireland offers another potential remedy - namely the act of partition itself. Applied to Kosovo, this would not only provide some compensation for what Serbs consider to be the province’s illegal confiscation back in 1999. But it also has the virtue of being a solution which accords with the facts on the ground - that Belgrade does not control the south Kosovo and Prishtina does not control the north.

Moreover, unlike in Northern Ireland, a decision to partition Kosovo would be final since the north does not contain a significant minority group that would later seek its reunification with southern Kosovo.

No doubt, there is resistance to this idea. Most Serbs would prefer to freeze the question of Kosovo’s status rather than partition it, pending some advantageous change in circumstances in the future.

However, the problem with this position is that the Albanians, who ultimately control Kosovo, are impatient to bring an end to their state of legal limbo. If they cannot gain recognition in negotiation with Serbia, they will ultimately pursue a unilateral solution, for which the obvious one is the unification of Kosovo with the recognised state of Albania. That in turn would compel Serbia to annex the north to save its Serb inhabitants from expulsion or absorption into an Albanian national state. The problems would not disappear but escalate.

Of course, the Serb public is not the only barrier to a solution based on partition. Albanians also object, for opposite reasons, as do most European diplomats who are allergic to changes in borders, especially along ethnic lines.

Ideally, those diplomats would shift their position and withdraw their support for Prishtina’s maximal position, which is politically untenable. At that point, they can look again at the case of Northern Ireland and the logic of partition as a solution to a mismatch of political and demographic boundaries. They may find they have much to learn.

In all societies there are issues that are rather being skipped. Certain...

The neoliberal path, started in 2001, has led to especially bad results in Serbi...

For centuries, the region was subsumed within the Ottoman and Hungarian Empires,...

"Serbia has returned to the systemic and anti-systemic position of the political...

In reality, Serbia is closer than ever to NATO. In the course of the last five y...